Cherice-splains: 10 Common Symptoms of Ableism

- MissCherizo

- Aug 10, 2019

- 7 min read

Updated: Oct 11, 2019

“It’s a good thing that there are people like you who are willing to work with those poor children, I couldn't do it!"

“You must be so patient to have to work with these kinds of children.”

“Mentally, he’s only 6 years old.”

“He’s severely autistic.”

“Her new baby has Down syndrome? How tragic!"

As someone who has worked with individuals with ASD and other developmental disabilities for the past five years, these are a few statements that I have heard from friends, parents, and even colleagues. You may think that some of these statements don't sound that bad at all and maybe you have even said some of these things yourself with good intentions. I am not here to make you or others feel bad -- as I think most people are just simply unaware there is anything wrong with these statements because we haven't really been educated about these things in our upbringing. That's why I am here to "Cherice-splain" what handicapism is so that you can become more aware -- and becoming more aware of your own behaviour and language is the first step to create a better world that celebrates diversity.

So moving on: there's sexism, racism... but what about ableism? Like sexism and racism, handicapism refers to the discrimination of individuals of a particular demographic.

“Ableism (also referred to as handicapism) has been defined “…as a set of assumptions and practices that promote the differential and unequal treatment of people because of apparent or assumed physical, mental, or behavioral differences.” (Bogdan & Biklen. 2013.)

The devaluation of people with disabilities start early in life: that being disabled is something that is undesirable and problematic, both for individuals and for society as a whole -- these ideologies can take root even before children enter school. Children may feel awkward or apprehensive about classmates who are disabled or otherwise different.

Overcoming this apprehension depends on a sustained effort by parents, teachers, and other adults to counter negative perceptions with positive experiences as well as personal contact between individuals with and without disability.

How you act and speak about people with disabilities matters.

So here are 10 most common symptoms of handicapism:

#1: Pity/Charity Mentality

This symptom is based on the belief that people with disabilities are to be pitied and that the quality of their lives is dependent on the kindness and charity of people without disabilities.

Examples:

“It’s so wonderful that there are people like you who are willing to work with those poor children” or "“You must be so patient to have to work with these kinds of children.”

Such statements stem from the perception that disability is tragic and that we should feel sorry for people with disabilities because they are “broken.” Fundraising initiatives on behalf of “the disabled” or “the handicapped” make deliberate use of the pity/charity mentality in order to solicit money. Fundraising initiatives target presumed feelings of sadness and guilt as they describe how people who are “suffering from” or are “victims of” one disability or another “need your help.”

Watch The Kids Are All Right, a documentary that addresses the pity/charity mentality and the Jerry Lewis telethon.

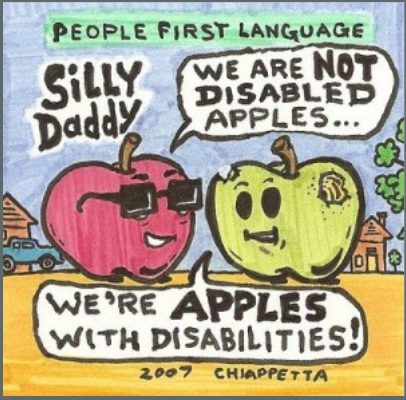

#2 Derogatory and Disability Focused Language

This is when you or someone else refers to a person with a disability in terms of his or her label rather than using person-first language.

Example:

Saying “I have a Down’s kid in my class” or “She’s a cerebral palsy student.”

The most important thing about Sam is that he’s Sam; and the most important thing about Jessica is that she’s Jessica – not that he has autism or that she has cerebral palsy. So, if we must describe Sam as a student with autism or Jessica as a teenager with cerebral palsy, we emphasize the person over the disability.

#3: Treating People with Disabilities like Children

Most of this stems from the belief that a person’s mental age or IQ score is more important than his or her chronological age.

Examples:

Referring to individuals by their mental ages.

Using childlike nicknames that are inappropriate for their age.

Talking down or baby talk (ie: "You're such a good boy aren't you?" to a teenager)

Physical affection that is inappropriate for their age.

Age-inappropriate social outings, activities, and interests.

Having expectations or standards relative to a person’s mental rather than chronological age. The portrayal of people with intellectual/developmental disabilities as possessing uncommon qualities of goodness, innocence, and forgiveness.

#4: A “Place” Mentality

This is the belief that people with intellectual/developmental disabilities are “better off with their own kind". evidenced in many ways, including:

Segregated (or “self-contained”) schools, classrooms, and living facilities (such as institutions)

Sheltered workshops instead of supported employment placements in the community

“Disabled-only” recreational activities, such as “disabled swim time,” “disabled bowling,” and “special” outings to in the community; and

Segregated sporting events such as the Special Olympics

When a woman chooses to join a women-only gym or an employee decides to join the company baseball team, they do so as a choice from the range of other available options. However, when Marcia, who has Down syndrome goes swimming during the disabled swim time at her local pool, or when Rob, who has cerebral palsy, participates in Special Olympics, they do so by default – because they were never given the opportunity to make those choices.

Perhaps Marcia would rather swim with the other children in her neighborhood during public swim time; perhaps Rob would rather play baseball with his brother in the local Little League. We will never know, however, because they were never given the opportunity to make those choices. The same thing applies to separate schools, residences, and other facilities – the people who use them (and/or their families) usually do so because there is no other option, not because they have made an informed choice.

#5: Linking Deviant Behaviour with Disabilities

Believing people with intellectual/developmental disabilities are:

...over-sexed and promiscuous;

...prone to criminal behavior;

...are dangerous and are a drain on societal resources

The children of people with intellectual/developmental disabilities will also be disabled.

These false beliefs can make community inclusion and participation difficult for individuals who have disabilities.

Example: Community members may feel opposed to the opening of a group home for people with intellectual/developmental disabilities in their neighborhood or claim that it is not "safe for families". An adult with an intellectual/developmental disability may asked not to frequent a local park “because a lot of children play here,” a deviance myth is almost always at the root of the problem.

#6: Handicapist “humour”

Today, most people understand that telling racist, sexist, or homophobic jokes is offensive to growing numbers of people. However, handicapist jokes continue to be acceptable to many, and appear to have tremendous staying power.

Example: Throwing words such as “disabled” or “retarded” around to describe someone doing something foolish.

What might seem like “harmless” fun continues to feed the social devaluation and segregation of people with developmental and other types of disabilities.

#7: Negative Assumptions Related to Atypical Communication

Individuals with disabilities who communicate in ways that do not involve speech (for example, through the use of picture symbols or an electronic device) are particularly vulnerable to handicapism, since it is easy for others to assume that they don’t understand what is being said or that they don’t have anything to say themselves.

Example: Ms. Larson is talking to Mr. Koul about Don, who is in the room with them and can hear what they are saying. “I’ve tried everything with Don,” says Ms. Larson, “and I’m at my wit’s end with him. He doesn’t seem motivated at all. What do you think I should do?"

#8: Access Barriers

Handicapism at a societal level is demonstrated when economic and political considerations get in the way of making buildings, streets, and homes accessible, useable, and safe for those with disabilities.

Examples of barriers for...

Individuals who use wheelchairs or other mobility devices:

Stairs

Curbs

Narrow doorways

Cluttered entrances (such as tables outside a café)

Individuals with physical disabilities:

Doorknobs that are difficult to grasp

Elevator buttons that are too high to be reached, difficult to push, or too small to see

Individuals who are blind or visually impaired:

Street lights and street signs

Building signs, door numbers

Menus

Printed information

Individuals with intellectual disability:

Printed instructions

Maps

Possible solutions:

Accessible buses, taxis, and other transportation services

Curb cuts and ramps

Buttons to open doors

Sound beepers at intersections

Fire alarms with flashing lights

Picture and/or braille menus

Closed captioning on TVs

Public events that include American Sign Language interpreters

#9. Presumption of Tragedy and Suffering

It’s important to remember that people who have always had a disability (like most people with intellectual/developmental disabilities) do not attach the same value as you do to “typical” physical, sensory, and intellectual capabilities.

Real story: In the 1990s when Tracy Latimer, a 12 year old Saskatchewan girl with cerebral palsy was killed by her father, Robert. Robert Latimer said he killed Tracy to end her suffering and constant pain. He was convicted of second-degree murder (even though it was clearly premeditated) and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Statements that can exemplify this belief:

“I’m amazed by how positive he is, despite what he’s been through with his disability.”

“I’m amazed at his sense of humor, considering what he’s been through,”

“I’d rather die than have an intellectual disability, be in a wheelchair, be blind or deaf,” and

“Her new baby has Down syndrome? What a tragedy!”

#10: Avoidance, Fear, Shame, and Embarrassment

Examples:

An adult tells a child not to stare at a person with a disability and leads the child away

An adult refuses to answer a child’s legitimate questions about disabilities.

The message “it isn’t polite to stare” can easily be interpreted by the child as “there is something wrong with that person and we need to get away from her.” Similarly, when adults ignore or avoid answering legitimate questions about disabilities, children often interpret this to mean that disability is an “off-limits” topic because it is shameful, scary, or embarrassing.

Positive Cycle of Change

Change is possible at both the individual and the societal level.

People without disabilities need to have opportunities to know individuals with disabilities, such as through inclusive practices in schools, community organizations, and workplaces.

When individuals with disabilities are included, myths and stereotypes are shattered and when they are shattered, society becomes more open to including persons who have disabilities.

You can make a difference.

Lots of love,

Cherice

Comentarios